- Home

- Isabel Allende

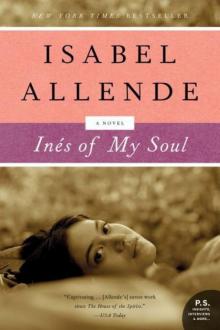

Ines of My Soul

Ines of My Soul Read online

Map

Praise

for Isabel Allende’s Inés of My Soul

“Vivid. . . . In Margaret Sayers Peden’s translation of Inés of My Soul, Allende’s reach is broad, scooping up politics, history, romance, and the supernatural. . . . Allende succeeds in resurrecting a woman from history and endowing her with the gravitas of a hero.”

—Maggie Galehouse, New York Times Book Review

“Historical fiction is always dangerous territory . . . but Allende has made this her métier. . . . Inés of My Soul is a complex and truly rich tale. . . . A compelling narrative, at turns lusty and wistful, with a sprinkling of braggadocio.”

—Baltimore Sun

“No contemporary author sows words together as deliberately or as beautifully as Allende. . . . [She] writes lyrically. . . . Surely the ghost of Inés Suárez is smiling broadly now that Allende has brought her back to life.”

—St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“A thorough and unflinching account of the conquest of Chile. . . . Allende’s talent (and ever-moving plot) keeps the pages turning. It’s a joy to see Inés triumph.”

—Rocky Mountain News

“Allende infuses this story with the emotional and sensual language that has characterized her novels going back to The House of the Spirits. . . . Inés of My Soul will gratify all Allende readers. They will find a story well told, a character deserving of a higher historical standing, and a vivid account of a fascinating historical episode that rarely makes the history books.”

—San Antonio Express-News

“Allende’s sweeping tale, conjured out of the mists of the past, recalls a fiery era that is tough to revisit. Yet Inés of My Soul makes it impossible to forget again.”

—Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Allende excels at immersing her readers in the sights, sounds, smells, and even flavors of an era. . . . [She] is a voluptuously visceral novelist. . . . Inés Suárez was a woman of great power, and Isabel Allende has honored her with an equally powerful novel.”

—Sunday Oregonian

“[An] image-rich journey through time. . . . [An] unforgettable tale of a powerful woman from Chilean history.”

—Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“Allende creates a riveting journey through a disturbing chapter of South American history. . . . Suárez’s story is so fabulous and life-affirming . . . that it simply captivates . . . a colorful and clear-eyed portrait of a woman and a country.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

Contents

Map

Praise

One: Europe, 1500–1537

Two: America, 1537–1540

Three: Journey to Chile, 1540–1541

Four: Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura, 1541–1543

Five: The Tragic Years 1542–1549

Six: The Chilean War, 1549–1553

Author’s Note

Bibliographical Note

P.S. Insights, interviews & More … *

About the author

About the book

Read on

Also by Isabel Allende

Copyright

About the Publisher

ONE

Europe, 1500–1537

I AM INÉS SUÁREZ, a townswoman of the loyal city of Santiago de Nueva Extremadura in the kingdom of Chile, writing in the year of Our Lord 1580. I am not sure of the exact date of my birth, but according to my mother, I was born following the famine and deadly plague that ravaged Spain upon the death of Philip the Handsome. I do not believe that the death of the king provoked the plague, as people said as they watched the progress of the funeral cortège, which left the odor of bitter almonds floating in the air for days, but one never knows. Queen Juana, still young and beautiful, traveled across Castile for more than two years, carrying her husband’s catafalque from one side of the country to the other, opening it from time to time to kiss her husband’s lips, hoping that he would revive.

Despite the embalmer’s emollients, the Handsome stank. When I came into the world, the unlucky queen, by then royally insane, was secluded in the palace at Tordesillas with the corpse of her consort. That means that my heart has beaten for at least seventy winters, and that I am destined to die before this Christmas. I could say that a Gypsy on the shores of the Río Jerte divined the date of my death, but that would be one of those untruths one reads in a book and then, because it is in print, appears to be true. All the Gypsy did was predict a long life for me, which they always do in return for a coin. It is my reckless heart that tells me the end is near.

I always knew that I would die an old woman, in peace and in my bed, like all the women of my family. That is why I never hesitated to confront danger, since no one is carried off to the other world before the appointed hour. “You will be dying a little old woman, I tell you, señorayyy,” Catalina would reassure me—her pleasant Peruvian Spanish trailing out the word—when the obstinate galloping hoofbeats I felt in my chest drove me to the ground. I have forgotten Catalina’s Quechua name, and now it is too late to ask because I buried her in the patio of my house many years ago, but I have absolute faith in the precision and veracity of her prophecies. Catalina entered my service in the ancient city of Cuzco, the jewel of the Incas, during the era of Francisco Pizarro, that fearless bastard who, if one listens to loose tongues, once herded pigs in Spain and ended up as the marqués gobernador of Peru, but was crushed by his ambition and multiple betrayals.

Such are the ironies of this new world of the Americas, where traditional laws have no bearing and society is completely scrambled: saints and sinners, whites, blacks, browns, Indians, mestizos, nobles, and peasants. Any one among us can find himself in chains, branded with red-hot iron, and the next day be elevated by a turn of fortune. I have lived more than forty years in the New World and still I am not accustomed to the lack of order, though I myself have benefited from it. Had I stayed in the town of my birth, I would today be an old, old woman, poor, and blind from tatting so much lace by the light of a candle. There I would be Inés, the seamstress on the street of the aqueduct. Here I am Doña Inés Suárez, a highly placed señora, widow of the Most Excellent Gobernador don Rodrigo de Quiroga, conquistador and founder of the kingdom of Chile.

So, I am at least seventy years old, as I was saying, years well lived, but my soul and my heart, still caught in a fissure of my youth, wonder what devilish thing has happened to my body. When I look at myself in my silver mirror, Rodrigo’s first gift to me when we were wed, I do not recognize the grandmother with a crown of white hair who looks back at me. Who is that person mocking the true Inés? I look more closely, with the hope of finding in the depths of the mirror the girl with braids and scraped knees I once was, the young girl who escaped to the back gardens to make love, the mature and passionate woman who slept wrapped in Rodrigo de Quiroga’s arms. They are all crouching back there, I am sure, but I cannot seem to see them. I do not ride my mare any longer, or wear my coat of mail and my sword, but it is not for lack of spirit—that I have always had more than enough of—it is only because my body has betrayed me. I have very little strength, my joints hurt, my bones are icy, and my sight is hazy. Without my scribe’s spectacles, which I had sent from Peru, I would not be able to write these pages. I wanted to go with Rodrigo—may God hold him in His holy bosom—in his last battle against the Mapuche nation, but he would not let me. He laughed. “You are very old for that, Inés.” “No more than you,” I replied, although that wasn’t true, he was several years younger than I. We believed we would never see each other again but we made our good-byes without tears, certain that we would be reunited in the next life. I had known for some time that Rodrigo’s days were numbered, even though he did everything he could to hide it. He never c

omplained, but bore the pain with clenched teeth, and only the cold sweat on his brow betrayed his suffering.

He was feverish when he set off, and he had a suppurating pustule on one leg that all my remedies and prayers had not cured. He was going to fulfill his desire to die like a soldier, in the heat of combat, not flat on his back in bed like an old man. I, on the other hand, wanted to be with him, to hold his head at that last instant, and to tell him how much I cherished the love he had lavished on me throughout our long lives.

“Look, Inés,” he told me, gesturing toward our lands, which spread out to the foothills of the cordillera. “All this, and the souls of hundreds of Indians, God has placed in our care. And as it is my obligation to fight the savages in the Araucanía, it is yours to protect the land and the Indians granted us to work it.”

His real reason for leaving was that he did not want me to witness the sad spectacle of his illness. He wanted to be remembered on horseback, in command of his brave men, fighting in the sacred region to the south of the Bío-Bío river, where the ferocious Mapuche have gathered to build up their forces. He was within his authority as captain, which is why I accepted his orders as the submissive wife I had never been. They had to carry him to the field of battle on a litter, and there his son-in-law, Martín Ruíz de Gamboa, tied him onto his horse, as they had the Cid, to terrify the enemy with his mere presence. He rode in the lead of his soldiers like a man crazed, defying danger and with my name on his lips, but he did not find the death he was seeking. They brought him back to me on an improvised palanquin, mortally ill. The poison of the tumor had spread through his body. Another man would have succumbed long before, but Rodrigo was strong, despite the ravages of illness and exhaustion of war. “I loved you from the first moment I saw you, Inés, and I will love you through all eternity,” he told me as he was dying, and added that he wanted to be buried without any fuss, though he did want thirty masses celebrated for the rest of his soul.

He died in this house, in my arms, on a warm summer afternoon. I saw Death, a little fuzzy, but unmistakable, as truly as I see the writing on this page. Then I called you, Isabel, to help me dress him, since Rodrigo was too proud to exhibit the decay of his illness before the servants. Only you, his daughter, and me, did he allow to outfit him in full armor and studded boots. Then we sat him in his favorite armchair, with his helmet and sword on his knees, to receive the sacraments of the Church and leave this earth with his dignity intact, just as he had lived. Death, which had not left his side and was waiting discreetly for us to finish our preparations, wrapped Rodrigo in her maternal arms and then made a sign to me to come receive my husband’s last breath. I leaned over him and kissed him on the lips, a lover’s kiss.

I could not fulfill Rodrigo’s wish to be sent off without a fuss; he was truly the most loved and respected man in Chile. The entire city of Santiago turned out to weep for him, and from other cities in the kingdom arrived countless expressions of grief. Years before, the populace had come out into the streets to celebrate his appointment as governor with flowers and harquebus salvos. We buried him, with the honors he deserved, in the church of Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes, which he and I had had built to the glory of the Most Holy Virgin, and where soon my bones, too, will rest. I have left enough money to the Mercedarios that for three hundred years they can devote a weekly mass to the rest of the soul of the noble hidalgo Don Rodrigo de Quiroga, valiant soldier of Spain, adelantado, conquistador, and twice gobernador of the kingdom of Chile, caballero of the Order of Santiago . . . my husband. These months without him have been eternal.

I must not get ahead of myself. If I do not narrate the events of my life with rigor and harmony, I will lose my way. Chronicles must follow the natural order of happenings, even though memory is a jumble of illogic. I write at night, on Rodrigo’s worktable, with his alpaca mantle wrapped around me. The fourth Baltasar watches over me, the great-grandson of the dog that came with me to Chile and lived beside me for fourteen years. That first Baltasar died in 1553—the same year Valdivia was killed—but he left me his descendants, all enormous, with clumsy feet and wiry coats.

This house is cold, despite carpets, curtains, tapestries, and the braziers the servants keep filled with live coals. You often complain, Isabel, that the heat here is suffocating; it must be that the cold is not in the air but inside me. That I can write down these memories and thoughts with paper and ink is owing to the good graces of the priest González de Marmolejo, who took the time, amid his labors of evangelizing savages and consoling Christians, to teach me to read. In those years, he was a chaplain, but later he became the first bishop of Chile, and also the wealthiest man in this kingdom. When he died, he took nothing with him to the tomb; instead, he left a trail of good works that had won him the people’s love. At the end, Rodrigo, the most generous of men, always said that one has only what one has given.

We should begin at the beginning, with my first memories. I was born in Plasencia, in the north of Extremadura, a border city steeped in war and religion. My grandfather’s house, where I grew up, sat at the distance of a harquebus shot from the cathedral, which was called La Vieja—the Old Lady—out of affection, not fact, for it had been there only since the fourteenth century. I grew up in the shadow of its strange tower covered with carved scales. I have never again seen it, or the wide wall that protects the city, the esplanade of the Plaza Mayor, the dark little alleys, the elegant mansions and arched galleries, or my grandfather’s small landholding, where my sister’s grandsons still live.

My grandfather, a cabinetmaker by trade, belonged to the Brotherhood of Vera-Cruz, an honor far above his social condition. Established in the oldest convent of the city, that brotherhood walked at the head of the holy week processions. My grandfather, wearing white gloves and a purple habit girdled with yellow, was one of the men chosen to carry the holy cross. Drops of blood spotted his tunic, blood from the flagellation he inflicted upon himself in order to share Christ’s suffering on the road to Golgotha. During holy week the shutters of houses were closed to block out the light of the sun, and people fasted and spoke in whispers. Life was reduced to prayers, sighs, confessions, and sacrifices. One Good Friday my sister, Asunción, who was then eleven, awoke with the stigmata of Christ on the palms of her hands, horrible open sores, and with her eyes rolled up toward the heavens. My mother slapped her twice, to bring her back to this world, and treated her hands with wads of spiderwebs and a strict diet of chamomile tea. Asunción was kept in the house until the wounds healed, and my mother forbade us to mention the matter because she did not want her daughter paraded from church to church like a monster from the fair. Asunción was not the only stigmatized girl in the region. Every year during holy week some girl suffered the same thing. She would levitate, emit the fragrance of roses or sprout wings, and at that point she would become the target of exuberant devotion from believers. As far as I know, all of them ended up in a convent as nuns except Asunción who, because of my mother’s precautions and the family’s silence, recovered from the miracle without consequences, married, and had several children, among them my niece Constanza, who will appear later in this account.

I remember the processions because it was in one of them that I met Juan, the man who would be my first husband. That was in 1526, the year Charles V wed his beautiful cousin Isabella of Portugal, whom he would love his whole life long, and the same year in which Suleiman the Magnificent, with his Turkish troops, penetrated into the very heart of Europe, threatening Christianity. Rumors of the Muslims’ cruelties terrorized the populace, and even then we thought we could see those fiendish hordes at the walls of Plasencia. That year religious fervor, whipped up by fear, reached the point of dementia.

In the procession, I was marching behind my family like a sleepwalker, light-headed from fasting, candle smoke, the smell of blood and incense, and the clamor of the prayers and moans of the flagellants. Then, in the midst of the crowd of robed and hooded penitents, I spied Juan. It would have

been impossible not to see him since he was a handsbreadth taller than any of the other men. He had the shoulders of a warrior, dark, curly hair, a Roman nose, and cat eyes, which returned my gaze with curiosity.

“Who is that?” I pointed him out to my mother, but in reply received a jab of her elbow and the unequivocal order to lower my eyes. I did not have a sweetheart because my grandfather had decided that I would remain unmarried and take care of him in his old age, my penance for having been born in the place of a much desired grandson. He did not have money for two dowries, and had decided that Asunción would have more opportunities to make a good alliance than I because she had the pale, opulent beauty that men prefer, and she was obedient. I, on the other hand, was pure bone and sinew, and stubborn as a mule besides. I took after my mother and my deceased grandmother, who were not noted for sweetness. It was said that my best attributes were my dark eyes and filly’s mane, but the same could be said of half the girls in Spain. I was, however, very skillful with my hands; there was no one in Plasencia and its environs who sewed and embroidered as tirelessly as I. With that skill, I had contributed to the upkeep of my family from the time I was eight, and I was saving for the dowry my grandfather did not plan to give me. I was determined to find a husband because I preferred a destiny of tilting with children to life with my ill-tempered grandfather.

That day during holy week, quite the opposite of obeying my mother, I threw back my mantilla and smiled at the stranger. So began my love affair with Juan, a native of Málaga. My grandfather opposed it at the beginning, and our home turned into a madhouse. Insults and plates flew, slammed doors cracked a wall, and had it not been for my mother, who put herself between us, my grandfather and I would have murdered each other. I waged such protracted war that in the end he yielded, out of pure exhaustion. I do not know what Juan saw in me, but it doesn’t matter; the fact is that soon after we met we had agreed to marry within the year, a period that would give him time to find work and for me to add to my meager dowry.

The Stories of Eva Luna

The Stories of Eva Luna The House of the Spirits

The House of the Spirits Paula

Paula Ines of My Soul

Ines of My Soul Of Love and Shadows

Of Love and Shadows Kingdom of the Golden Dragon

Kingdom of the Golden Dragon Daughter of Fortune

Daughter of Fortune City of the Beasts

City of the Beasts Maya's Notebook

Maya's Notebook Eva Luna

Eva Luna Zorro

Zorro In the Midst of Winter

In the Midst of Winter Forest of the Pygmies

Forest of the Pygmies My Invented Country: A Nostalgic Journey Through Chile

My Invented Country: A Nostalgic Journey Through Chile The Japanese Lover

The Japanese Lover Portrait in Sepia

Portrait in Sepia Island Beneath the Sea

Island Beneath the Sea The Soul of a Woman

The Soul of a Woman A Long Petal of the Sea

A Long Petal of the Sea Ines of My Soul: A Novel

Ines of My Soul: A Novel The Sum of Our Days

The Sum of Our Days